A Thousand Brains

A Thousand Brains by Jeff Hawkins presents an interesting and new theory of intelligence. At times, it feels a bit self-aggrandizing (Hawkins has an axe to grind about, The sections on existential risk to humanity feel less well-thought out.

That said, I thought the Thousand Brains theory itself feels like a big step forward. Intuitively, it's a great 'gears-level' model for how neural networks might work, and how they might be improved. I learned a lot about how brains actually work by reading this book.

I hadn't realized this but Hawkins was one of the founders of Palm Computing, but left the company to work on neuroscience full-time.

The big idea: today's ML models lack a 'model' they are pursuing, they merely throw larger and larger neural networks at more data. Hawkins presents a model where ML and AI could work more like brains by combining thousands of different individual models, and then having a 'voting' step between them.

New Brain vs Old Brain

Apparently the brain evolved by adding more and more mutations over the years, creating new and interesting structures. These are primarily the "old" brain which houses a bunch of our basic functions for things like breathing, regulation, etc. Something odd happened in our evolution though, we discovered a new circuit (the Neo-Cortex), and the brain just started producing more and more of that one single circuit.

The Neo-cortex

You can think about the neo-cortex as being a set of 'new, general purpose circuits which have evolved to take care of high-level cognitive functions. It consists of many layered connections which form 'cortical columns' of networks. Unlike other parts of the brain, the neo-cortex didn't evolve for any particular purpose, it just exists as general purpose wiring. Neo-cortexes in blind people will re-wire so that brain function is used to connect other senses. Indeed, this is a key part of the general purpose cognition.

Hawkins proposes that the neo-cortex is all about forming predictions and models of the world. These models don't rise to your notice until reality stops matching the model! An example is the stapler on his desk: he didn't know anything about how it feels, how long it is, and what the click to staple something together looks like. But now, he would immediately know if any of those things didn't match his predictive model.

This section reinforced how similar neural nets are to actual computing. It's not a far stretch to say that they are almost exactly trying to mimic actual brain behavior!

ML ignores dendritic activation

That said, ML models aren't perfect! There are a few parts of a neuron: the axon, dendrites, and synapses. Synapses fire, and can activate neurons, which then transmit those signals to the other parts of the body via Axons.

Hawkins claims his big insight is that dendritic activation is used to 'prime' a response as each individual neuron builds a model of the world. Dendritic activation accounts for 90% of neural cells... and yet most ML models don't leverage it, since we didn't really understand why it exists.

He argues that by including these models in our approach to ML, we'll be able to get better results.

Where vs What

Hawkins argues that there are actually two types of neurons. "Where" neurons help provide a reference frame in relation to your body. "What" neurons help identify what an object is in relation to the world.

Specialized regions in the brain

there's a predominant theory that certain regions are used for language learning, and that language is somehow special. If that were true, we'd see specialized versions of the brain for them!

Do we see that? Kinda. It's unclear what part of the brain is used for what. In terms of the regions they look just like any other part of the neocortex. That said, regions related to language only appear on the left side of the brain!

Being an expert is mostly about finding a good reference frame that you can use to frame and connect various facts! Even if multiple people with the same fact, they may interpret them differently through different reference frames!

Thousand brains theory says: a single cortical column can learn a model over time by integrating its inputs. If that is true, can removing a single cortical column remove someone's concept of a thing?!

The Thousand Brain theory in a Nutshell

Individual cortical columns build different models. They then 'vote' on the results of those models to bring a single unified view to the brain (referred to as the binding problem)

The analogy is that each column would have an individual map of different towns they could be in, and a set of observations (e.g. I'm near a coffeeshop, I'm near a library). The columns then all compare their observations and list of maps, and narrow down to a single town based upon their observations. The beauty of this system is that it doesn't require all neurons to be online, nor does it require they all have the same size map. It's very distributed (in the same way that no one person knows how to manufacture a pencil)

Optical illusions are an interesting example of this. In the vase or faces illusion, you brain can either perceive a vase or a face, but it's difficult to see both at once.

What ML is missing: reference frames

Today's ML models are sort of like specific circuits. They are very good at doing specific things (playing go, classifying images, etc). However, they don't do a good job of solving general purpose problems. Hawkins argues that new ML techniques require new approaches to solve the problem of general intelligence. A mouse has a great general purpose brain in that it can learn, the brain is just small and low-powered.

Consciousness

How does the theory relate to consciousness?

Hawkins views consciousness like this...

Consciousness is when you have a string of memories that drive your actions. imagine you had washed your car in the morning, and then somebody had wiped the memory from your brain. you would say "I wasn't conscious while doing it!" but if you were shown a video of yourself doing it, you'd probably also say that you did it 'unconsciously'. Hawkins argues that really what drives consciousness is a sequence of memories driving for some goal, which is totally compatible with the thousand brain theory.

I'm not sure how much I buy this exactly, but it does seem to make sense at first blush. Maybe arguing about consciousness in the first place doesn't really matter in the end.

Existential Risk

Hawkins isn't too worried about existential risk in the same way that Nick Bostrom is in Superintelligence. He argues that a pure 'thinking machine' won't have innate goals. And it won't do things without us instructing it to do so.

I'm not sure how much I agree with this. Hawkin's analysis seems much more surface-level vs Bostrom's.

Models in action

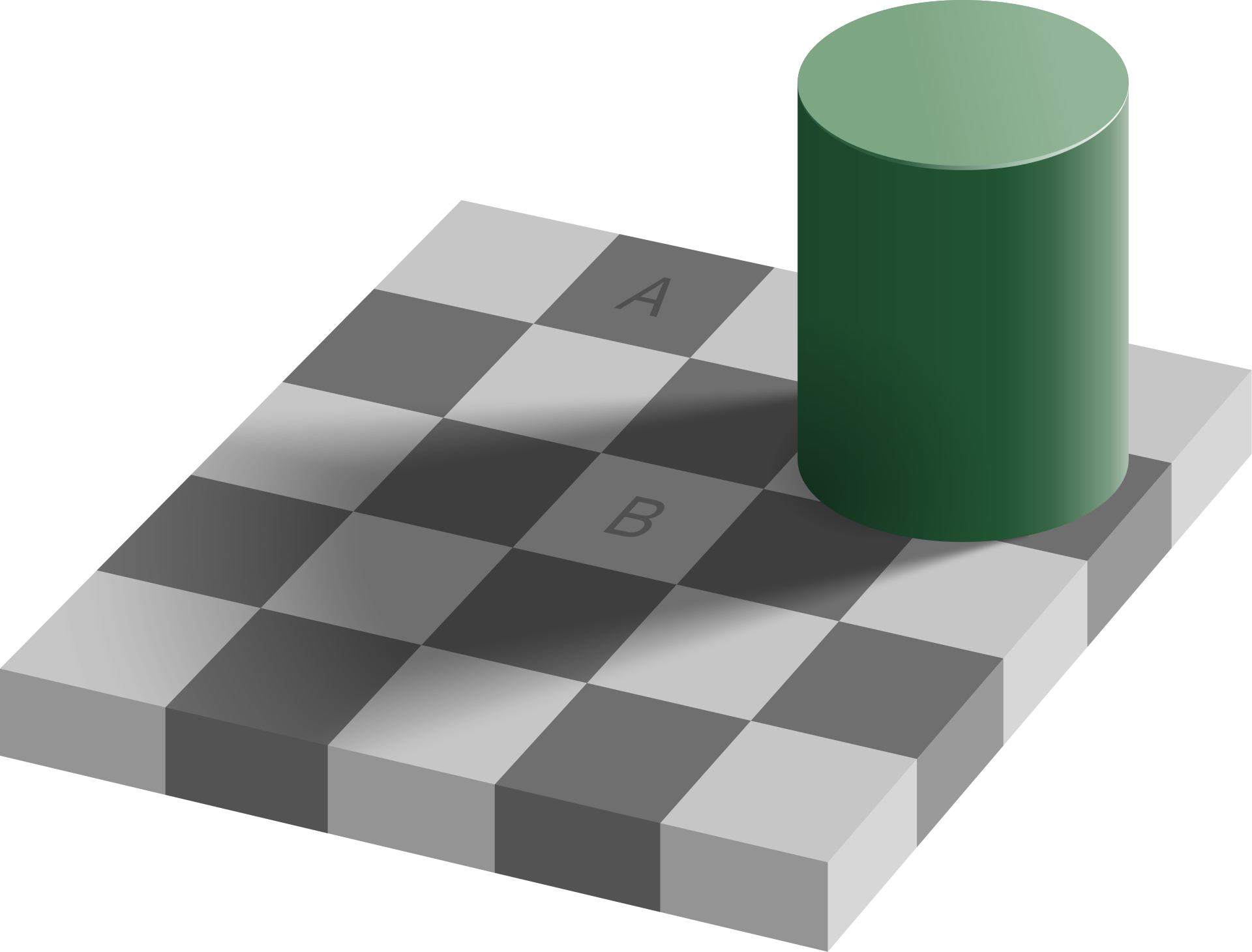

A good example of seeing two models in action is this checkerboard illusion (via wikipedia)

The squares labeled A and B are actually the same color! How can this be?

We have two competing models: the model of a checkerboard which must alternate black and white squares. And then the shadow model, that a shadow should be darker than they items around it. In this case, the checkerboard model wins out, making us perceive the B square to be lighter than A, even if it isn't.

Self reproducing models

Models which we teach to others (every child should get a good education) are inherently more viral. This is the same idea of a meme that Dawkins presents.

Honestly the rest of the book trended more towards the political + existential risks to humanity. If you're interested in the threats that AI poses here, I'd check out Nick Bostrom's Superintelligence.