High Bit-rate People

Have you ever noticed how some people talk a lot, but say very little? Where you leave a conversation with them, and can't even remember the main takeaways?

During my time at YC this past summer, I interacted with hundreds of different founders. Nearly all of them needed to improve the way they describe "what the company does".

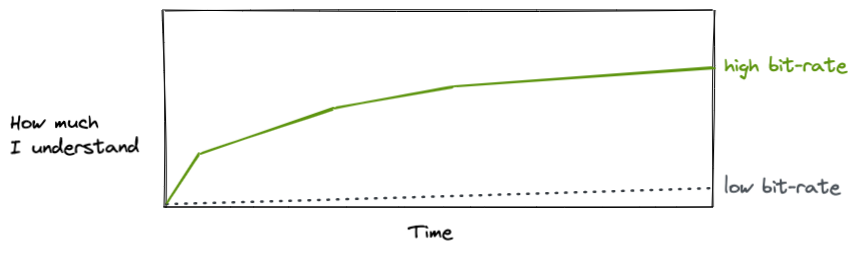

As a founder, you want to strive for what I call 'high bit-rate' communication. For every minute of speaking, is your listener getting a lot of information? [1]

Founders from academia and big companies often have a lot of habits to unlearn here. You don't get extra points for a 2,000 word essay when two sentences will do. You don't look clever when you use obscure jargon. And you definitely won't get me to invest if I can't understand what your company does.

During YC, we worked with founders on achieving high bit-rate communication explicitly for pitching investors. But there's actually a much more important reason to do it.

As you scale your company, low bit-rate communication translates as low clarity. Leaders who can't clearly communicate the company's goals can't execute against them. They'll spin you into confusion and random activity.

So if there's one skill I can encourage founders to instill in their company from day one, it's a practice of crisp, high bit-rate communication.

The good news is that communication is a practical skill, just like anything else. In the same way that you'd practice scales to become a better musician, you can work to practice effective communication.

What follows are the top pieces of feedback I give to founders as they practice their pitches.

1. Your pitch isn't a mystery novel

There shouldn't no "grand reveals" or Shamalan-esque plot twists in your pitch. Don't bury the lede. Start with the most important point up front.

Your mental model should be: "I have about thirty seconds to grab the listener's attention. That's it." You must use those thirty seconds to convey the most important information possible.

I see too many founders trying to build up their pitch from vague statements and platitudes. They wait until five minutes in to actually explain what their business does. In doing so, they end up losing the listener.

This isn't a new concept. Generations of consultants have realized that they need to start with the most important idea, and then add supporting evidence. Founders should do the same.

2. Use numbers

Numbers don't lie.

If I ask you: "What's your revenue goal for the next month?" there's many different answers you could give.

Too often, I get an answer like this...

It depends on how you measure it, as there are different ways where we generate revenue. We have recurring revenue that comes from customer subscription plans, we have one-off payments from an "initiation fee" that we charge users, and we have affiliates that contribute a subset of referral revenue. Our goal is to double revenue from each of these sources in the next month.

This response doesn't actually answer my question.

When I'd really prefer an answer like this...

Our goal is to grow monthly revenue from 15k to 30k next month.

This answer is abundantly clear, and it immediately grounds the conversation. I know how big the business is currently, what the goals are, and how much growth they are shooting for. And then, it allows me to ask follow-up questions around where that revenue will come from.

It's okay to be uncertain. It's okay to have risks and blockers. But instead of giving me a lengthy explanation that backs into a number, start with a number first. Then give me context.

3. Paint a picture in my head

When it comes to your investor pitch, the strongest thing you can do is paint a picture in my head. Focus on describing your product in the most tangible way possible.

If you're building Uber, don't say: "We're a last-mile logistics marketplace between gig workers and customers". Do say: "Uber lets you call a car from your phone in minutes."

Tie to physical objects, and include a handful of details. If your product targets students, say what age. If it targets a certain geo, mention it. If you sell to businesses, tell me what size and industry.

The more specific you can be, the better I'll be able to imagine your user and product. [2]

4. Avoid jargon, cut words

Imagine you have 30 seconds to explain something to a smart friend.

You aren't going to spend a ton of time teaching them jargon and lingo that's specific to your field. Instead, you're going to focus on the stuff that matters (the high bit-rate stuff!). You'd use language they already know.

Founders should do the same as they explain their company. Avoid jargon and acronyms unless they are absolutely essential. Cut out any words that don't add to the listeners understanding.

5. Highlight "surprise"

The best pitches I hear explicitly focus on the unexpected. They tell me something that I can't already tell. Here's a bad example:

Worldwide banking is a massive market.

This sentence gives me zero information. It's something I already knew.

Highlighting surprise comes from emphasizing information that I likely don't know. Here's a great example:

With our group therapy product, we see an 80% repeat visit rate. That's in comparison to a 15% repeat rate of a standard therapist.

Hearing this immediately gets my attention. I didn't realize the standard therapist rate was so low. This startup must really be onto something!

Consider what's "common knowledge", and remove that from your pitch. Focus on the stuff that's not widely known.

6. Write it down

One of Jeff Bezos' most famous directives at Amazon was banning the use of powerpoint in meetings. He decreed that instead, all meetings should start with a reading period of a six-page memo.

There's a reason that Bezos set this principle: writing forces clarity of thought. Skilled presenters can throw together a slide deck and muddle through a presentation. Writing front-loads the intent.

Part of the reason for this is that the english language is quite redundant. In the Art of Doing Science and Engineering, Hamming notes:

Notice in English how much more often different words have the same sounds ("there" and "their" for example) than words that have the same spelling but different sounds ("record" as a noun or a verb and "tear" as a tear in the eye vs tear in the dress).

You've probably noticed this in your own life too. You can read a transcript more quickly than you can listen to a podcast. And you can get higher-density information from a transcript edited for clarity than the raw speech.

There's a few ancillary benefits of banning powerpoint as well...

Written memos are durable. A new employee can understand the thinking that went into decisions made years ago. They aren't missing the oral context.

Written memos separate bias. Instead of basing decisions on the quality of the presenter, it's easier to focus on the quality of ideas.

7. Compression

It's a little known fact that MIT requires all CS undergrads take an oral communication class. That decision was based upon years of feedback from alumni who said "nobody ever taught us how to present!"

Ten years later, I remember one particular exercise that consistently improves clarity.

First, our professor asked us to give an impromptu presentation in five minutes. After we'd finished, he asked for the same presentation, but this time in 3 minutes. When we'd finished a second time, he finally asked for the same content in 60s, without adjusting our pace of speaking.

The clarity of presentations blew me away. Instead of rambling, the presenters still managed to convey 90% of the important information in a fraction of the time.

I encourage founders to try a similar type of compression. Explain your pitch in 5 minutes, then 3 minutes, then 1 minute, then two sentences.

The content you decide to omit probably isn't that important to begin with.

8. Pause.

This last point is really counterintuitive.

Founders who communicate more information end up pausing much more as well. To make each word count, you have to utilize the whitespace. Let each point you're making sink in.

One trick I like to tell founders is to "do your best Obama impression". Speaking more slowly helps them establish an aire of gravitas.

The written analog to this is how you structure your paragraph and sentences. Great writing has a 'rhythm' to it that allows the reader to easily chunk together different ideas. No run-on sentences. No chunky paragraphs.

Getting an ear for high bit-rate

Because we learn to communicate at such a young age, most people rarely learn to examine and critique their communication.

Most of my college courses put a focus on solving problems. They never taught me to explain "here's why these problems are important" to an audience.

The good news is that becoming a high bit-rate person is very achievable with focus and attention.

Over the course of Segment's founding journey, I saw each of us hone our ability to communicate ideas. We relentlessly critiqued one another's blog posts and strategy docs in search of better clarity. To this day, I still consider myself a student of high bit-rate communication.

If you're giving a talk, practice it ahead of time. Try to compress it down to just the 60 seconds of core ideas.

Anytime you write an email, go back through it, and try cutting half the words.

If you've just learned a concept, try explaining it to as many friends as you can. Watch for the moments where their eyes light up.

Once you get an ear for it, you won't go back.

“I didn't have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.”

-Mark Twain

Thanks to Tim Brady and Sam Hinkie for reading drafts of this essay.

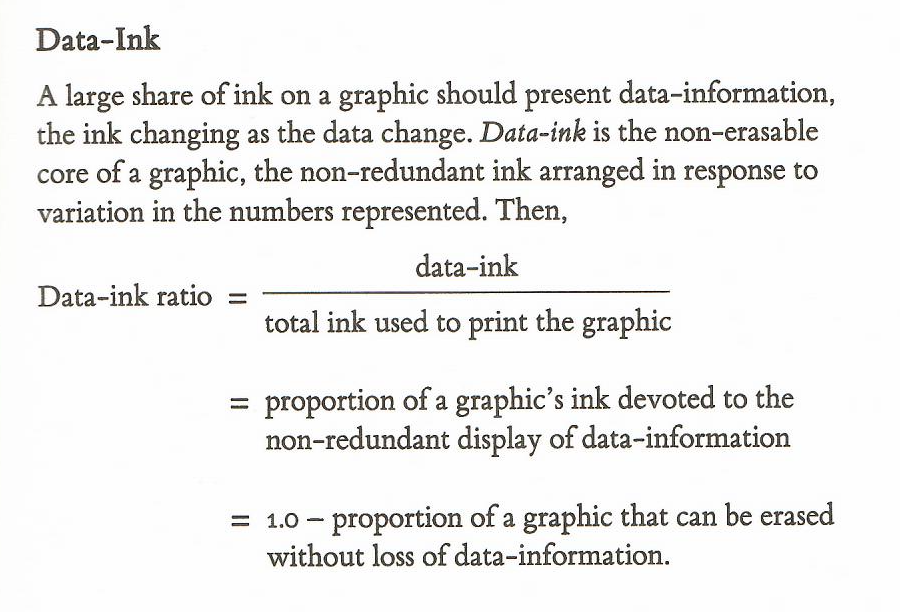

[1]: For visual displays of information, Tufte refers to this as the "data-ink" ratio.

[2]: For some examples of what not to do, check out the websites of enterprise software companies that IPO'd in 2006-2009. See if you can understand what they do.