Sense of Style

If your 7th-grade experience looked anything like mine, you probably studied grammar rules. You learned about structuring five-paragraph essays. Maybe you even memorized the do's and don'ts of style guides.

But like many other parts of middle school, all of that advice was thrown out the window once we hit adulthood.

Whether it's a twitter thread or blog post, you rarely see this style of formulaic writing. Instead, the most popular authors tend to be funny, engaging, and easy to understand.

So why are our best style guides 50+ years old? Did the english language really peak before the moon landing?

In Sense of Style, Stephen Pinker sets out to write "the style guide for the 21st century". He wants to help authors write with clarity, expression, and just a hint of panache.

You should probably read this book if you're excited about...

- seeing examples of incredible writing

- the intricacies of grammar, syntax, and word choice

- gaining a deeper appreciation for the english language

- how written communication actually happens

In the backdrop of all of this... I couldn't help but ponder how writing styles will evolve in the world of LLMs. Pinker doesn't mention it at all (the book came out in 2015). However, Sense of Style helps us answer questions around why ChatGPT can sometimes feel so stale.

As one quick aside before we get started: it's tricky to cite a book which cites other books. Pinker liberally cites examples from other works. Just know that all the specific instances here come from the book.

What makes writing 'great' anyway?

Understanding great writing comes from developing an 'ear' for it. The english language has evolved so much over the centuries that you can't really invent it from first principles. Like a sommelier would practice identifying the notes of a particular wine, aspiring writers should hone their skills by studying great prose.

To start us off, Pinker opens with a few different excerpts of great writing. My favorite example comes from the opening lines of Richard Dawkins' Unweaving The Rainbow

We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Arabia. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively exceeds the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.

- Richard Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow

This paragraph is good. Very good. It's the kind of thing where you read it once and it sticks with you for days. Why is that?

Well, it starts with a paradox. Instead of some sort of boring platitude or expected intro, Dawkins dives right in. The fact that we should die makes us lucky? Those two sentences never go together. They make you wonder what kind of strange resolution could come next.

This paragraph also includes a number of specific examples. "Outnumber the sand grains of Arabia" conjures a more concrete sense of vastness than "big" or "massive" ever could. "Greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton" carries more weight than "genius" ever would. Great writers paint a specific picture in your mind. Specific examples are the reason that "the ivory chess set fell off the table" is easier to imagine than "the set fell off the table".

And there's unusual word choice: "unborn ghosts" and "in the teeth of these stupefying odds". These phrases are so rarely heard together that you can't help but sit upright in your chair and take notice. You read and savor them.

The best writers also cut like a film director would. They focus on the subject in very particular ways. Describing the scene in simple, concrete terms. They don't do a ton to setup the scene, they just start rolling.

Great writers generally use simple words over complicated ones. But they relax that rule when they have the chance to create a phrase which is a little more memorable and punchy. Take the following obituary for Dear Abby which appeared in the NYT:

Pauline Phillips, a California housewife who nearly 60 years ago, seeking something more meaningful than mah-jongg, transformed herself into the syndicated columnist Dear Abby—and in so doing became a trusted, tart-tongued adviser to tens of millions—died on Wednesday in Minneapolis. . . .

With her comic and flinty yet fundamentally sympathetic voice, Mrs. Phillips helped wrestle the advice column from its weepy Victorian past into a hard-nosed 20th-century present. . . .

Notice flinty and hard-nosed. Both words are uncommon, but they don't require the use of a dictionary.

Even better is when the word follows the proper phonesthetics, the "feeling" of the sound.

Take the following two examples...

a sea of sexy models and provocative cover lines

vs.

a sea of voluptuous models and titillating cover lines

Per Pinker–"Voluptuous has a voluptuous give-and-take between the lips and the tongue, and titillating also gives the tongue a workout while titillating the ear with a coincidental but unignorable overlap with a naughty word."

Even though a dictionary might tell you these sentences are equivalent, to the listener they are radically different.

All of this to say: great writing keeps the reader guessing. It focuses their attention on areas of importance, and constantly highlights the unexpected. It stays away from platitudes, and varies the sentence structure and word choice.

Classic style

At this point you might be thinking: "sure, I can appreciate Dawkins–but I'm looking for something I can actually apply." What should be our north star?

Pinker argues that the best "default writing style" is classic style.

Classic style states that the focus of a writer should be 'seeing the world'. It's the writer's job to direct the reader's gaze to things they might not have noticed and allow them to see it for themselves. Classic style "succeeds when it aligns language with the truth, the proof of success being clarity and simplicity."

It's not your job to convince, and you don't have to share your reactions to whatever you're observing. Instead, you accompany the reader, and let them connect the dots for themselves.

When I think of classic style, my mind immediately jumps to Paul Graham's essays. As I read them, it feels like he's there in the chair next to me, reading them aloud. I rarely have to backtrack and go back to an earlier sentence. Each builds upon the next. Richard Feynman and Malcom Gladwell mastered this style as well.

Because the focus of classic style is clarity, there is no recommended form. Writers leverage whatever tools they need to get the job done. Unlike a business memo (which follows what Pinker calls practical style), the writer's primary job is to compose and curate the writing, with a focus on content which is non-obvious.

The hallmarks of classic style...

Does not try to argue, and instead should merely highlight facts about the world. It's not the author's job to persuade, just to point to the truth.

Clear and straightforward. It avoids any form of jargon, and prefers simple words to complex ones.

Avoid 'really' – avoid using some sort of qualifier in cases where you don't want to add a qualification to the scale. Saying 'Jim is an honest man' is very different than 'Jim is a very honest man'. Mark Twain had a quote that instead of writing 'very' anywhere, you should just write 'damn', and then let your editor remove it all.

Avoid quotes – avoid using 'scare quotes', it indicates that you aren't really comfortable using the language that you're using... so why are you using it in the first place? The three use cases where it can hold are when 1) you are literally quoting someone 2) you are referring to a word as a word 3) you are using the term but indicating your disagreement with it.

Treats the reader as an equal. It's not condescending, and allows the reader to draw their own conclusions. The examples of classic style feel like a good friend explaining something to you over drinks. "Classic writing makes the reader feel like a genius. Bad writing makes the reader feel like a dunce."

There's no signposting. You'd never tell a friend "I'm about to tell you three different things about trees...", you'd just dive right in. Classic style gets straight to the point. Authors don't talk about what they want to say, they just say it.

Bad: This chapter discusses the factors that cause names to rise and fall in popularity. Better: What makes a name rise and fall in popularity?

Confident, does not hedge. How many times have you read a newspaper article that is endlessly couched in "allegedly" and "reportedly". Classic style instead counts on common sense and says what it needs to. "Any adversary who is unscrupulous enough to give the least charitable reading to an unhedged statement will find an opening to attack the writer in a thicket of hedged ones anyway."

Avoid cliches and vagaries. It's easy to include sentences which convey little-to-no information. Cut them, or re-phrase.

Bad: When Americans are told about foreign politics, their eyes glaze over. Better: Ever tried to explain to a New Yorker the finer points of Slovakian coalition politics? I have. He almost needed an adrenaline shot to come out of the coma.

Avoid abstract nouns (e.g. 'level', 'strategy', 'issues', 'perspective'). Instead, just write directly.

Bad: I have serious doubts that trying to amend the Constitution would work on an actual level. On the aspirational level, however, a constitutional amendment strategy may be more valuable. Better: I doubt that trying to amend the Constitution would actually succeed, but it may be valuable to aspire to it.

Aside from these rules of the road, Pinker also offers two pieces of advice to improve our writing.

Advice 1: read it out loud – we naturally tend to pause and shift intonation while reading sentences out loud. It's easier to hear the verbal sticking points once they are uttered out loud.

Advice 2: take a break – after you've written a draft put it away for awhile. Taking time away allows you to naturally forget. A musician friend says this is exactly what he does while mixing songs. He'll shelve a song for months, to come back and realize which parts are the most interesting.

This advice sounds incredibly straightforward, but it tends to be very hard to achieve in practice. Most of us tend to get wrapped up in adding words and jargon that end up obscuring our points. Classic style says "forget all the noise, just focus on the truth".

How we perceive language: webs, trees, and strings

Pinker is a psycholinguist. So he spends a decent chunk of the book describing how we perceive language, and how different phrasings of the same concept change our understanding. In particular how grammar is used to better communicate.

I had expected the section on grammar to be endlessly boring, but Pinker asks us to ponder: "why bother with grammar in the first place?"

"[Grammar] should be thought of instead as one of the extraordinary adaptations in the living world: our species’ solution to the problem of getting complicated thoughts from one head into another. Thinking of grammar as the original sharing app makes it much more interesting and much more useful. By understanding how the various features of grammar are designed to make sharing possible, we can put them to use in writing more clearly, correctly, and gracefully."

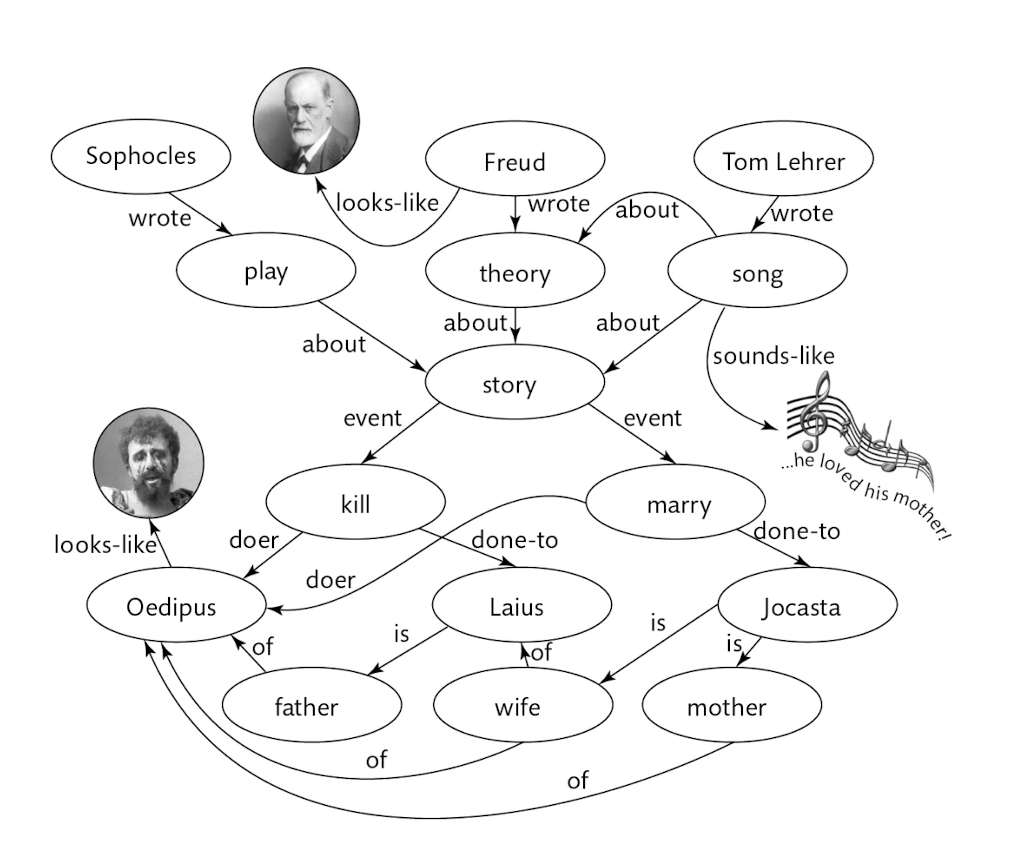

When communicating, we start with a web of ideas. In our heads, there exists a loose web of words and concepts. You can think of it as a set of nodes with edges describing their relationships to one another.

If you've read Shakespeare's Oedipus Rex, your web might look something like this...

There's all manner of concepts in here, some of which are directly related to the play, and some of which connect to other concepts we might hold (now you know what Freud looks like).

We hold these graphs in our head and traverse them, effortlessly gliding from one idea to another. Sometimes we'll spot connections, and strengthen that edge.

But here's the trouble... you can't easily just "transfer a graph to another person". It'd take eons to enumerate all the nodes and edges in your graph. The closest thing we have to a digitized format are neural network weights... and those aren't easy for people to understand.

Instead, we convey information via a string of words that comes from our mouth and fingers. This is the 'serialized' format. It's the text you're reading right now.

Now the trouble occurs when the reader (or listener) then has to work backwards. They must fit that set of words into their own tree, and linking the concepts in their own mind. This is syntax.

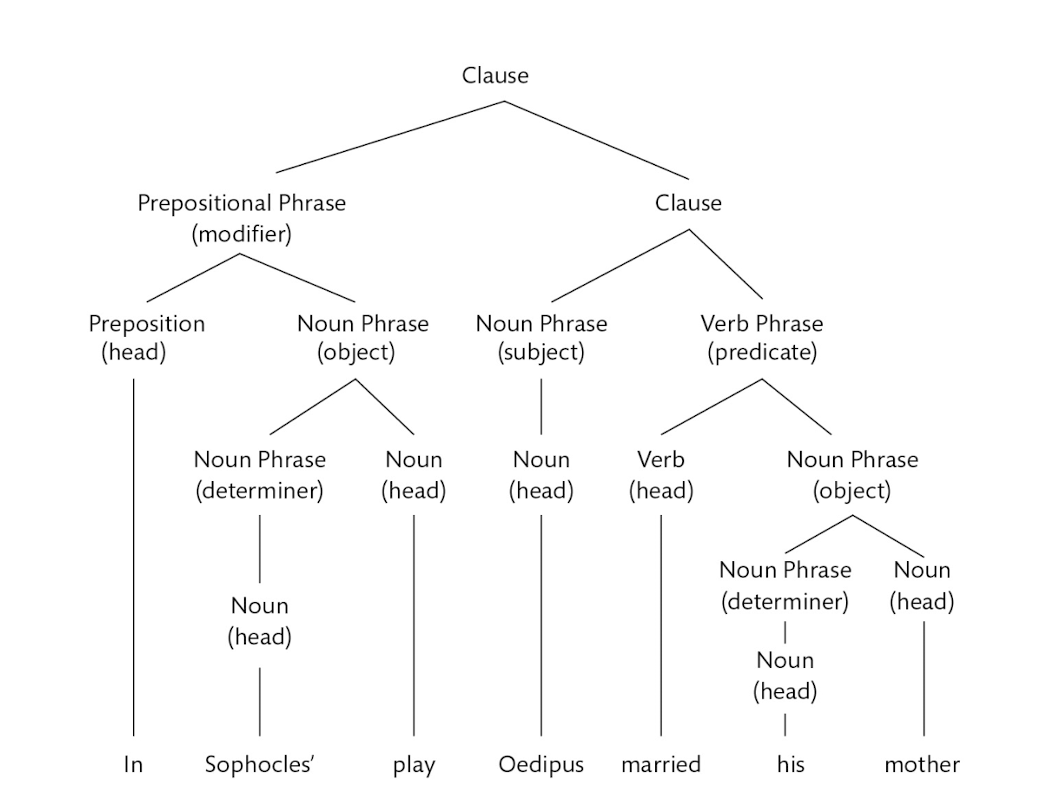

Just as programming has abstract syntax trees for defining language, Pinker thinks of english as having it's own set of syntax trees (shown in the diagram below).

The best way to read these is from the bottom-up. The english sentence is given in left-to-right form, and each word bubbles up into different phrases and clauses to create the whole.

Pinker argues that the main reason english is so challenging is because writing syntax from left-to-right has to do two separate things at once

- it's the code to convey to who did what, to whom

- it's the sequence of early-to-late processing in the reader's mind

English must simultaneously encode both the order that events happened and how words are related together. It's a writer's job to constantly reconcile

Most of grammar and punctuation exists to disambiguate these two things. Grammar helps us understand how related words together. Punctuation helps us understand how the pauses in "eats, shoots, and leaves" differ from "eats shoots and leaves".

So how we communicate clearly using trees? It actually looks a lot like writing clean code.

Take the following "bad" example from the book

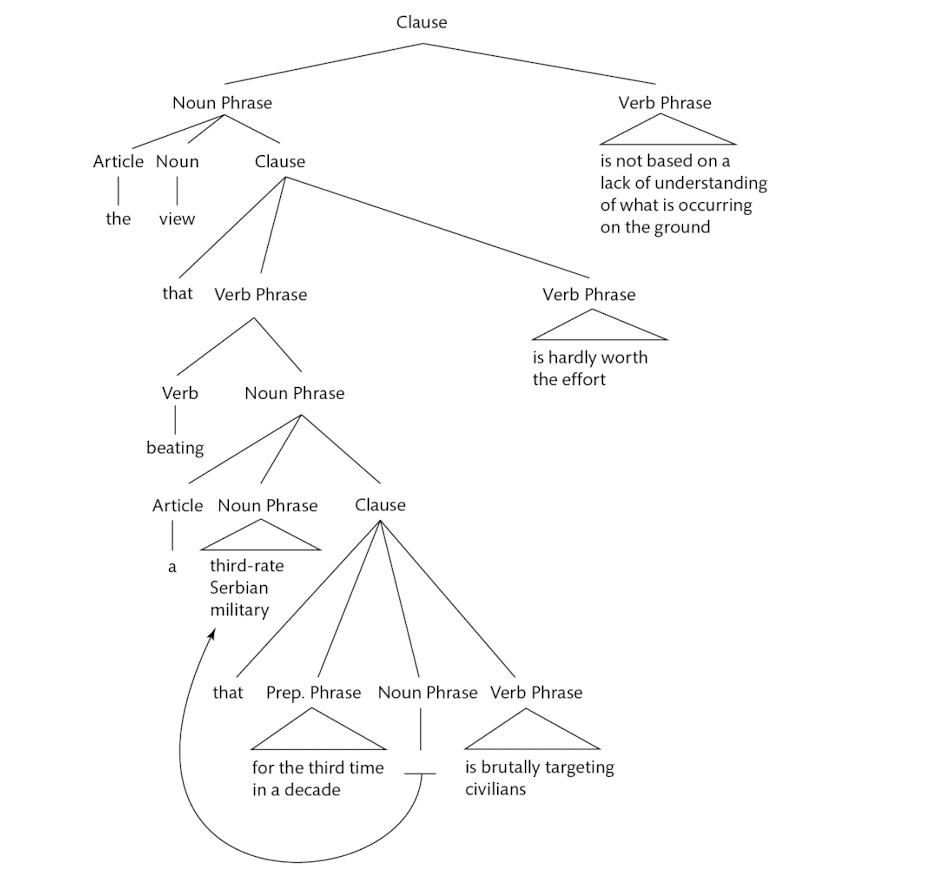

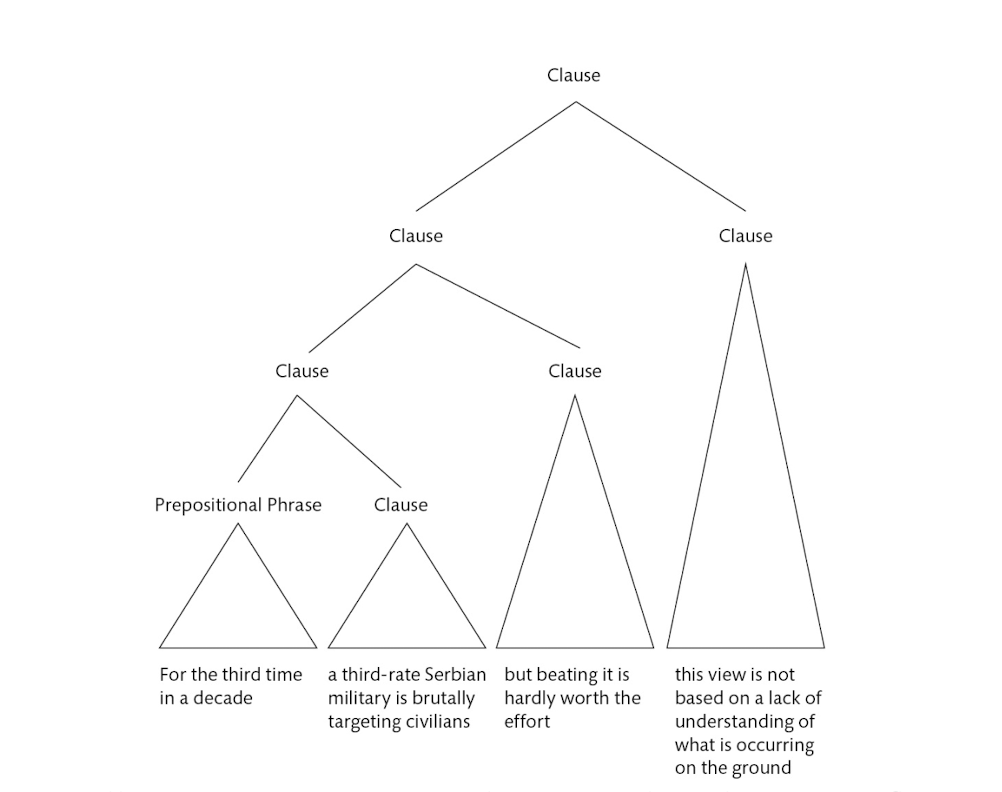

The view that beating a third-rate Serbian military that for the third time in a decade is brutally targeting civilians is hardly worth the effort is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

- Bob Dole, Aim Straight at the Target: Indict Milosevic, Boston Globe, May 23, 1999.

The problem with this sentence is that it creates "too big of a stack", to quote programming parlance. The reader has to keep track of a "view", a "third-rate Serbian military", and "third time in a decade" before understanding that it's the military targeting civilians. The stack then unwinds to to "beating" this entity. Followed by it being hardly worth the effort. Followed yet again by it not being a view based in reality.

If we chart the 'tree' here, we can clearly see where this sentence is going wrong

Our first problem is that this sentence has too many "deeply-nested" structures. Looking at this tree, there is a ton of state we have to keep in our heads to understand what is going on.

The primary subject of the sentence is "a third-rate Serbian military", and it is referred to after a lot of context: "the view that beating". Making things worse, the next clause –"for the third time in a decade... ...is brutally targeting civilians"–refers back to that same subject.

If we were to re-write this problematic sentence, a better version might look like this...

For the third time in a decade, a third-rate Serbian military is brutally targeting civilians, but beating it is hardly worth the effort; this view is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

It's not that much better (I still have trouble following it). But it does allow you to easily split up the clauses into separate pieces. These can be split as their own individual sentences, or omitted entirely.

See how in the new structure starts with a simple prepositional phrase, and then immediately gets to the main subject of the sentence?

It's a bit easier to follow, and doesn't leave the reader wondering where the sentence is about to go. Commas and semicolons connect these phrases to signal that the last clause (this view...) should be separate from the whole.

The moral of all this is that writing for people is hard and under-appreciated work. Readers need to reconstruct your graph of mental nodes from just some serialized strings of text. Unlike modern protocols, the English Language developed over centuries and has ambiguous syntax. Punctuation can with some of these problems, but it's not perfect. After all, people aren't computers.

LLMs

Well... what about computers?

If you've been playing around with LLMs, you've probably noticed that while the output is 'good', it never tends to be 'great'. It always feels a little flat, putting factual accuracy ahead of flair.

One reason for this is that the training data is filled with far more Reddit than Capote. But we can take that a step further.

The fundamental goal of an LLM is to predict the most likely next token in a sequence. But if we've learned anything from Pinker, it's the idea that writing well can't just follow the most likely path.

Great writers highlight unlikely combinations that still make sense.

GPT-4 has what's known as a "temperature" setting which allows you to adjust how likely it is to choose tokens from the long-tail of the distribution. But the problem is that increasing temperature won't necessarily give you more interesting combinations... it will create more randomness across the board.

That said, the transformer architecture actually seems like it would mirror many of the concepts that lead to good writing:

- in training, the weights of the model effectively code for the 'web of ideas'. The embedding for 'king' is close to the embedding for 'queen' + 'male'. Clearly there's some deeper concepts embedded here.

- phrases are connected by their proximity to one another. The big insight of the attention mechanism was being able to dynamically adjust the weight of different tokens in relation to one another.

Finally there's the question of interpretability. Somewhere in the LLM we've built the web... but in the output, all we see is the string of text. Re-creating that state is nearly impossible (just as you can't inspect my mental state either), but how far can we go by serializing it to and from english?

At its best, Sense of Style is an in-depth examination of the patchwork human-to-human API we know as English. At its worst, it’s a bunch of tedious grammar rules. And at the very least, it will give you a deeper appreciation for the delights of great writing.