The Accidental Superpower

I found The Accidental Superpower off a few different Twitter threads. It’s written by Peter Zeihan, a geopolitical analyst with a delightfully down to earth writing style.

The book discusses America’s rise to power and how it came about as a result of its incredibly lucky and bountiful geography. Zeihan makes bold predictions for how the next 20-40 years will play out, and also shares a few interesting models for how to think of national behaviors.

As an extra note, I’d highly recommend listening to the audio version which is narrated by Zeihan himself.

Bretton Woods

The book starts off with the Bretton Woods Agreement, established in 1944 after WWII.

To set the stage… the allied forces had forced a turning point in WWII with a successful victory at Normandy. Nearly everyone had suffered massive losses both in people and in naval forces. Everyone that is, except America.

At the agreement were economic delegates from all of the major allied powers, including John Maynard Keynes. The goal was to establish a new world order rooted in financial stability.

There was nervous anticipation for what the U.S. would do. America would clearly emerge as the front-runner of the war, relatively untouched by invasion at home and with its navy largely intact.

Instead of enforcing regional military rule across the globe and enforcing a tax, the U.S. took the opposite turn. Officials agreed to establish both the IMF and the World Bank, and peg the currency to the U.S. Dollar.

As a critical part of the agreement, the U.S. guaranteed safe free trade between nations, and it would support that trade with its navy.

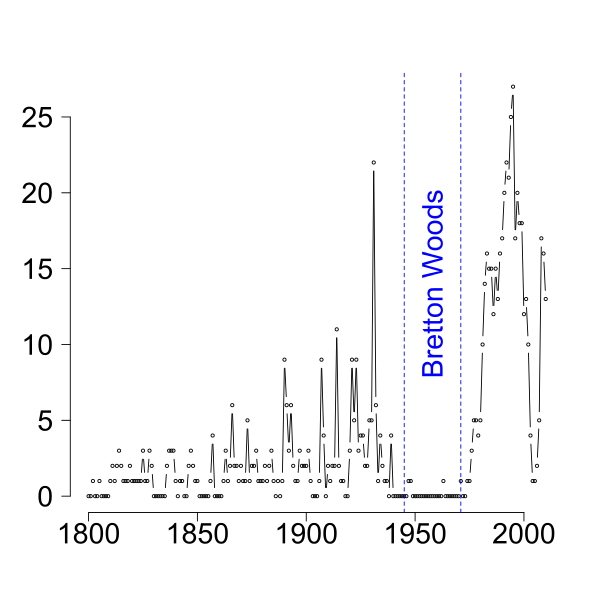

Interestingly, it had the right effect. When graphing global banking crises, they disappear after Bretton Woods went into effect until the gold standard was eliminated.

I hadn’t known at all about the Bretton Woods agreement before the book, and always just sort of assumed that free trade + peaceful interactions were more of an outcome of the modern age than an explicit decision.

Rivers open up trade

The book then cycles to the fact that economies are fundamentally driven by access to rivers.

Since the dawn of human history, rivers have defined the plains for irrigation and the routes we have to access trade.

The Nile was this breadbasket for a long time. It had rapids to the north and south, and big deserts to the east and west. The Nile protected the ancient Egyptians for millennia until ship technology was good enough to brave the rapids.

This is an important point for America too. America has access to the largest set of navigable waterways in the world.

There’s a story in the book of an apple farmer who can only transport 3000 apples per week. Suddenly he has a mule pull a barge, and then he can transport 10x that much, simply by floating the barge down the river.

Deep Water Navigation

While rivers open up trade within a country, deep water navigation across oceans can open up trade on a much bigger scale. The invention of the sextant and the compass began to allow nations with lots of sea access, but little in the way of river access (the British and Portuguese) to rise to power.

This was in stark contrast to the Swedish, who had man-powered boats with big crews (more people == more oars). They traveled much further inland and would more often pillage the native peoples than attempt to trade with them.

Notably, America has incredible access to trade in terms of deep water navigation. It is one of only a handful of nations with port access to both the Atlantic and Pacific markets. And its lack of land-based surface area makes it very difficult to attack.

Shale

I learned quite a bit about the Shale revolution in the U.S. (which is still an active debate topic of public policy).

Historically, the U.S. has been largely dependent on other countries for its source of oil.

But, recently new technology has opened up the ability for the U.S. to produce more oil than it consumes: horizontal drilling and fracking. Between these two innovations, large amounts of oil fields found in the U.S. are suddenly able to produce significant amounts of oil domestically… so much so that Zeihan predicts the U.S. will no longer need foreign oil.

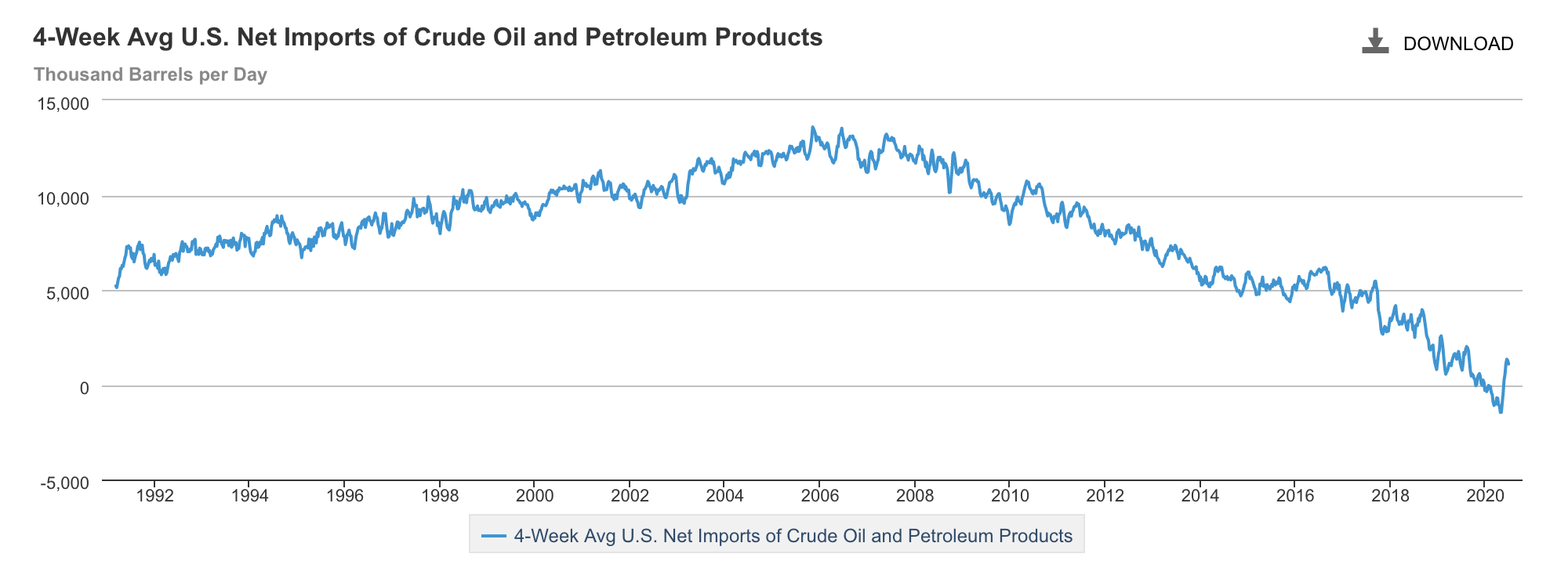

Looking at the data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, we see this prediction came true.

In the early part of this year (2020), the U.S. went from being a net importer of oil to a net exporter. A trend which has reliably continued since 2006.

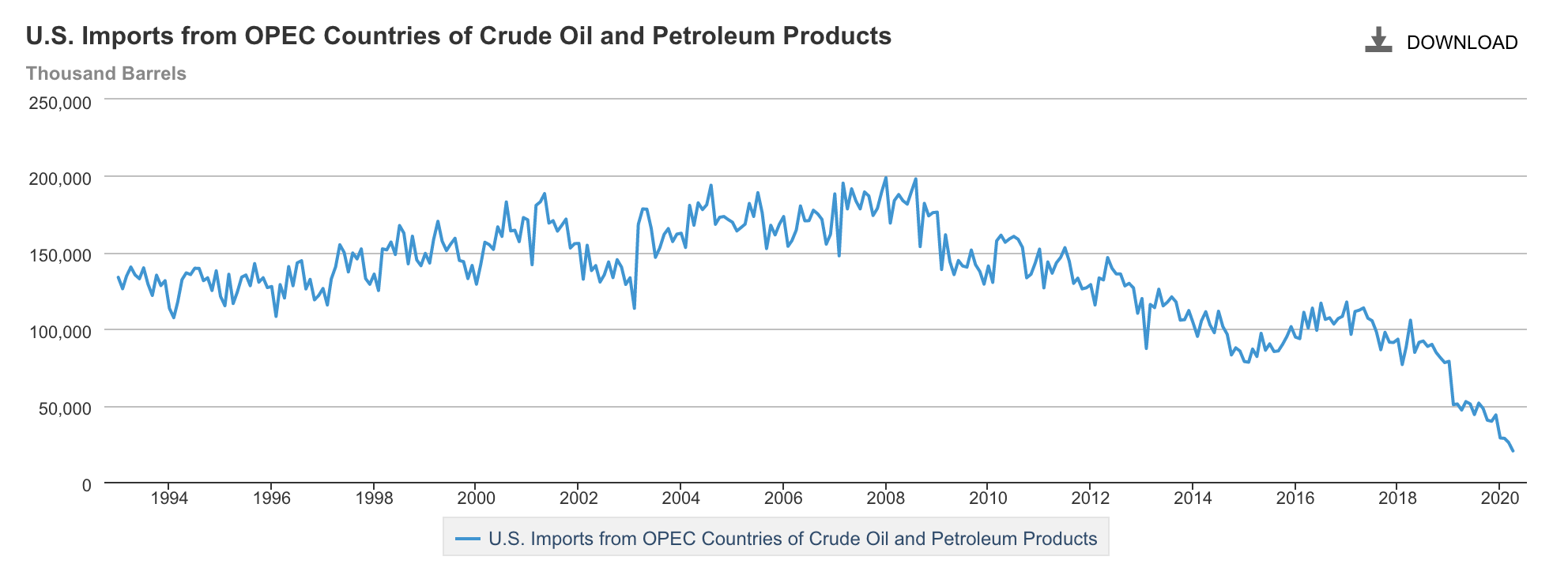

Additionally, the U.S. has substantially dropped its import volume from the Persian Gulf and most notably, from OPEC countries.

Demographics rule

Zeihan presents a model of demographics that consists of four phases in a person’s life.

- **Kids **(no production, mid-consumption) — kids don’t produce anything, as they aren’t working, but they do consume quite a few of a countries resources.

- **Young workers **(mid-production, high-consumption) — young workers are at their peak consumption. they take out mortgages and loans to buy houses and cars, and are using lines of credit to build their families

- Older worker (high production, mid-low consumption) — older workers have hit their peak of production, but are consuming less. they are helping fund the consumption of the younger workers, and have reached a level of expertise that causes them to have the highest output.

- Retiree (zero production, mid-low consumption off savings) — when a population retires, their production falls off a cliff, from highest to zero. retirees stop pushing capital back into the economy in favor of instead

Generally countries have to be growing slightly to avoid this “fall off a cliff” scenario. If their population is stagnating or shrinking, countries will experience economic recession even in the face of other tailwinds.

The Baby Boomer generation created an outsized population of producers, then consumers, then retirees. Zeihan argues that everyone else is so globally tied to the U.S., that they will see a recession as the boomers retire.

Another interesting point: Zeihan argues that immigration is incredibly good for a country. Effectively the country doesn’t have to bear the cost of educating kids, while gaining highly productive young and older workers.

General models for countries

Time will tell how many of these predictions come true, but I was struck by a few different frameworks and models by how countries operate.

**Can you be sufficient with what you have? **If the answer is yes, you won’t care that much about trade or international relations and will turn inward. This is precisely the situation the U.S. is beginning to find itself in (this finding also reminded me of Jane Jacob’s observations on import replacement). As America no longer needs to import oil or food, we no longer really need the Bretton Woods agreement securing trade either. Zeihan doesn’t think China will rise to power because it lacks a food production system outside of rice production.

**Immigrants are key. **Immigrants bring production, growth, and innovation. Failing to allow immigrants into your country will limit your economic growth and saddle you with additional costs.

**Demographic changes will rule and create ripple effects. **The biggest lesson I hadn’t really considered earlier is how much demographics and population curves drive overall growth. To know whether a country is due for a recession, simply look at its population curves.