Coding Agents in Feb 2026

I recently joined my friends Diana, Harj, Garry, and Jared on the YC Lightcone Podcast to discuss coding agents. I had a lot of fun with the conversation, but afterwards I couldn't help but feel like I hadn't gotten into the details of how I'm using the different agents. And ultimately, the details matter a lot!

In this post, I'd like to dive into some more of the nuance around the models.

As quick background: I helped launch the Codex web product, and have worked pretty extensively with Claude Code in the intervening months. I've come to the conclusion that both models have different strengths and weaknesses related to their training mix.

The biggest change to my workflow is that my time is now the biggest consideration. I'm primarily picking my coding agent as a function of how much time I have, and how long I want it to run autonomously (is it better to get a 80% draft done overnight, or try and work collaboratively with the model during the day?). Depending on the type of feature and how mission critical it seems, I'll reach for different tools. I pay for all of Claude Max, ChatGPT Pro, and Cursor Pro+, and it's some of the best money I spend anywhere.

Here's my point-in-time snapshot of what I'm doing today (Feb, 2026). It all changes quite quickly so I don't expect this to stay relevant over time.

Guiding principles

To use coding agents well, you must understand context.

It's easy to fool yourself into thinking that the coding agents are magical models. They have read all of the internet, developed deep levels of intuition for the structure of codebases, and been trained to write extremely correct code.

But at the end of the day, the agent is doing next token prediction. And each token must fit in a context window.

There are a bunch of corollaries that fall out of that...

- Your work needs to somehow be chunked. If the problem you are trying to solve is 'too big' for the context window, the agent is going to spin on it for a long time and give you poor results.

- Compaction is a lossy technique. When deciding what to compact and how, the agent is going to make choices on which information to include and omit. Maybe it does a good job, maybe it doesn't! In my experience, more compaction tends to lead to more degradation in performance.

- Externalizing context into the filesystem (e.g. a plan doc with stages which are checked or not) allows agents to selectively read and remember without filling up the full context of the conversation. This is helpful for resuming tasks and continuing to be context-efficient.

- Stay in the 'smart' half of the context window. It's generally easier to train on short-context data vs long-context data. Results will tend to be better when the context window is 'less full'. Dex Horthy calls this staying out of the dumb zone.

- You don't know what you don't know. If the agent somehow misses a relevant file or package, it might really go in a direction you didn't anticipate. If it's not in the context window, there's no way to know. Your codebase's structure can help this, as can 'progressive disclosure' of parts of the architecture. OpenAI has a nice blog post about structuring many different markdown files to do this well.

As a result, model performance and speed is governed both by the pure performance of the model, but also by how it is able to manage multiple context windows and delegate to sub-agents or teams of agents.

Opus: context whiz, better tool-use, more human

Claude Code is my regular driver for planning, orchestrating my terminal, and managing git/github operations. I'll typically use it for creating an initial plan, scripting against things on my laptop, and also for explaining how parts of the codebase work.

Opus has been trained to work across context windows extremely efficiently, so using it with Claude Code feels much faster than using Codex. You'll notice Opus frequently spinning up multiple sub-agents simultaneously, whether it's to Explore parts of the codebase or handle multiple simultaneous Task calls. The explore tool uses Haiku so it is very fast at processing a lot of tokens, and handing the relevant context back to Opus.

What's more, Opus has been trained well to use the tools on my laptop: gh, git, various MCP servers. Occasionally I will use the /chrome extension to verify a bug, which works pretty well, but can be slow and buggy.

I also find the permission model of Claude Code is easier to understand. There's a bunch of prefixes for commands you can run. With Codex models it's harder to whitelist individual CLI tools because the model will often "script" against these commands in bash (for ... gh).

I've talked a lot about Claude Code being an incredible harness for the model, and there are a lot of small things that it does which make it nice to use: updating the terminal title to be task-relevant, showing the current PR in the statusline, the little status messages.

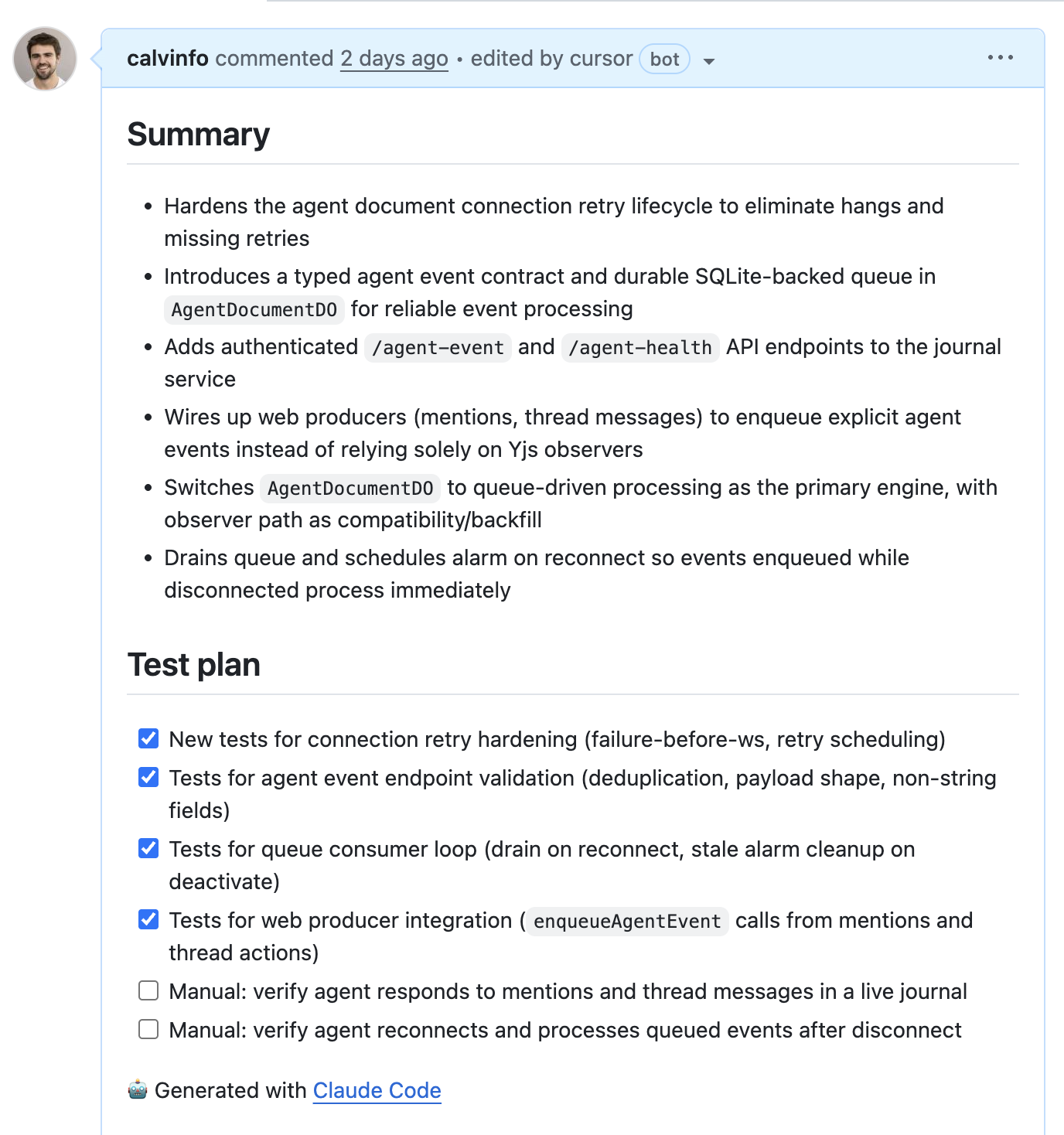

Finally, a lot of folks talk about "personality" of the model. I don't buy into this too much, but find Opus is more willing to give me human-understandable PR descriptions and detailed architecture diagrams which are easy for me to understand.

If I am asking for an explanation about how some piece of the code is structured, I'll typically use Claude Code.

I also find Opus is a little more 'creative' in terms of suggesting things that I may have forgotten to mention. This is actually a very nice property when creating plans, I'll invariably leave some aspect out, and Opus can help point out areas of ambiguity.

Codex: way fewer bugs

Where Codex shines is correctness of code. Other folks who are pushing the models a lot seem to agree.

I run on GPT-5.3-Codex-xhigh or high, and the Codex code just straight up has fewer bugs. Opus will frequently add a set of React components which pass unit tests, but then the model just straight forgets to add it to the top-level <App> which gets rendered. There's obvious off-by-one errors which don't get caught. Dangling references or race conditions which are subtle and hard to spot.

For a long time, I thought there was a negligible difference between the two models. But after seeing enough PRs with automated reviews from Codex and Cursor's Bugbot, I've realized that OpenAI's model is superior in terms of the code it writes. If you'd like to A/B test this yourself, just check out a branch and run /code-review in Claude Code vs /review in Codex.

Unfortunately, Codex is slow.

The biggest reason for this is that it's not delegating tasks across context windows, though I get the sense that the latency between tokens might also be higher. I have been running with the experimental subagent support (toggle in /experimental) which does manage to do this and it works well, though perhaps not as seamlessly as Claude. The parallelism still isn't there quite yet.

The net result between the two is that I'll start with Claude Code and keep that open as a pane, then flip to Codex when I'm ready to actually start the coding.

Every so often I will still leverage Opus, but it mostly comes down to leveraging tool use (/chrome to debug, make stylized frontend changes).

Useful things

A few caveats: I am working on greenfield codebases. They are much much smaller than any production codebase I've worked in, and are relatively token-efficient.

Repo structure -- all of my repos have a plans/ folder, with numbered plans as I ask the agents to implement things. Typically I'll also have an apps/ folder for different services I'm running. I'm using turborepo to manage monorepos in typescript, and bun for fast installs.

Ghostty -- Mitchellh's terminal is fantastic. Fast, native, and constantly improving. For a little while I was running multiple Claude/Codex instances in tmux, but now I just use multiple panes within the same terminal tab.

Next.js on Vercel, APIs on Cloudflare Durable Objects -- I've mostly been leveraging Cloudflare Durable Objects for APIs and storage. The idea that you can partition your database ahead of time, wake it up on demand, and not have to worry a ton about concurrent writes is a really wonderful property. In a time of agents acting on small pieces of data, I can't help but feel that it just makes sense from an infra perspective. Cloudflare is also leaning into this with their cloudflare/actors library which bundles up compute with small bits of co-located storage.

Worktrees -- since all of my code is relatively lightweight and small, I'm able to leverage parallel worktrees by using bun install and then bun run dev across each one to verify locally. I have a worktree skill which copies any relevant plans, env vars, and other updates, and starts a new branch. I didn't really use worktrees prior to coding agents (I was mostly a branch guy) but having them work in parallel and letting Claude Code manage the syntax is a godsend.

Plan, Implement, Review -- I almost always have the model start with a plan. This is useful for two reasons: 1) it externalizes the context beyond a single context window 2) it allows me to review or interrogate what was done. If an agent stops for some reason, I can always start a new context window and tell it to resume the plan.

Preview deploys -- every branch gets a fresh Web + API deploy. It makes running in parallel and quickly testing branches a breeze. It's way harder to work without this.

Cursor Bugbot and Codex Code Review -- I still spot-check the code, and make sure I understand it from an architecture level, but increasingly I am not reading every line of every PR. I rely on agents to spot subtle bugs (they are far better at it than I am). For awhile I was using Claude Code, Cursor's Bugbot, and Codex. Claude Code didn't seem to catch real issues for me. Since then, I've settled mostly on Cursor as the default option since you can tell when it's working, though I find the results of Codex are good too.

Skills

Today I have a bunch of skills and a shared AGENTS.md/CLAUDE.md defined in a repo I call claudefiles. My rule for adding skills is not to do it prematurely, but only if I find myself settling into a workflow after a few times.

While I find the AGENTS/CLAUDE.md are handy for steering the model overall, skills are for two specific reasons:

- They let you chain and automate workflows. This is my (and generally?) the most common use case for skills. I'll typically want to start with a plan, then implement in stages, then review. Why not have skills for each of these processes? Then I can have a meta skill which implements them all in order (see below).

- They help you split context windows -- at least in Claude Code, invoking a skill can happen in a new context window if you set

context: fork. This is really handy if you have a single context window for the 'master orchestrator', and then sub-agents which go and do parts of a task. The orchestrator can keep sub-agents working, and process outputs as they finish.

Skills are also great because they are very context efficient. Unlike MCP calls (which take up thousands of tokens), skills tend to be ~50-100 tokens.

Automating with skills

Early on in my journey with Claude Code, I was intrigued by the idea of skills marketplaces. That you could just install great frontend-design / security detail / architecture review.

After working for awhile, I've mostly abandoned skills that anyone else has written. Instead, I start doing things manually, then think about how I want to automate them. Over time, I've ended up building a lot of time-saving automation.

Here's how my use of skills has evolved. I say this not to tell you what the "golden path" for which skills to use, but more as an illustrative example of how you might automate more of what you are doing with them. Here's my journey.

The first skill I added was obvious, rather than tell the model to commit and push (in half a dozen different ways) add a /commit skill which is borrowed directly from Claude Code.

Then I realized if I wanted agents working in separate worktrees, I should probably just rely on Claude Code to manage it. So I added a /worktree skill which creates a new worktree, keyed off the plan's number (e.g. 00034-add-user-auth).

The next thing I noticed myself doing was always doing a plan step, then implement the plan in stages. I'd first clear the context window, and then say "implement the next stage of the plan, then /commit". But it became clear this was a good candidate for a skill: /implement which basically does exactly that.

Of course, just typing /implement in succession is annoying, so I added an /implement-all which looks at the current worktree path, ties it to the plan number, and then implements everything in stages. Sometimes when I'm running overnight, I'll leverage the /ralph-loop just to keep it going until all stages are done. I also added a local /codex-review which basically spawns a codex --review process to run the review.

/implement-all was working pretty well, but I wasn't really closing the loop on addressing feedback from the models in CI. I'd get these bug reports from Cursor + Codex indicating that there was still more work to do, even after each phase of the plan had succeeded.

So I added an /address-bugs skill which looks at the GitHub API, searches for Cursor + Codex comments since the last commit, and then attempts to verify and fix them. Then it will fix those bugs.

Finally I realized this was just working in a loop, so I added a /pr-pass, which runs at the end of /implement-all. It essentially 1) pushes to the remote 2) waits for all CI to pass 3) runs /address-bugs and then optionally goes to step 1 until it's finished.

These were all nice speedups, and I realized they were helping me with a lot of bookkeeping. So I also added a /focus skill which looks at my plans dir, my outstanding PRs, and my worktrees to help refresh my memory and keep me on track.

Importantly, I don't think I would've had any success trying to start with this process. But by building it over time and noticing little areas where I could automate, it's significantly improved my workflow.

Stuff I didn't mention here

I gave the Codex App a shot recently, and I was pleasantly surprised at the attention to detail and the little touches related to it. I have yet to move my workflow over fully from the CLI tools since I appreciate the flexibility of the terminal. Still, I like the idea. I tried giving Cowork a spin as well, and had a hard time getting it to work properly. In each case I think the sandboxing model makes a big difference!

Occasionally I will use the web interface for async jobs, though I find right now I'm more and more tied to the CLI. This is different from what I was doing 6 months ago, where I was mostly using Cursor and the built-in agent or extensions.

I've picked up pencil.dev for working on frontend UI. The deployment model is fascinating if nothing else, it shells out to your local Claude Code (able to re-use your existing subscription).

I'm still feeling like I should be using a more well-defined issue tracker. David Cramer's Dex seems to be promising, in a similar spirit to Steve Yegge's beads. Both feel like a little more than I need, but perhaps I'm just not in the right workflows.

I am not really using Playwright or other automated e2e MCPs.

Free advice to the labs

No one asked, but here it is :)

Anthropic

Model: Like I mentioned before, the Opus models totally shine on feeling human, working with engineering tools, splitting context in the right ways to achieve good parallelism, and taking liberty on things "you might have forgotten". Where they don't is in the code correctness. I'd love to see an 'Opus Strict' mode, where some base model has really been RL'd to achieve better performance. Opus is where I start, but Codex writes all my code. If I was budget constrained, I'd probably pick Codex.

Product harness: This is the one area where I basically have no notes. Boris and Cat have better ideas than I do mostly. My two requests:

- Adopt agent skills so I don't have to do this dumb symlinking between a bunch of directories. I think Anthropic has little incentive to make this happen, but it'd be nice for those of us who flex between the two CLIs.

- Publish the output format for

--stream-json. I'm probably not alone in terms of being interested in running Claude Code in a sandbox on behalf of users. But I am worried the format will change out from underneath me. Depending on the sandbox, it's also been annoying to setup the right pathing properly for Claude Code, whereas the other CLI tools (Codex, Cursor, Gemini) seem to install without issue.

OpenAI

Model: The number one thing the OpenAI models can do to improve is figure out how to split across context windows and delegate to sub-agents. I'm using the experimental sub-agent version. There's also this "more than what you asked for" concept that Opus manages to accomplish during planning that would be useful.

Product harness: I have a lot of small feedback here that I think would go a long way (and maybe some of this is out of date)...

- I still don't understand the sandboxing model vs Claude Code's, and because the model often tends to script, I end up needing to give a lot of approvals. Since the models are so determined, I worry a bit about running in

--yolomode. - Like Claude Code, add some sort of "user guide" that ships with the CLI so I can ask questions about things like where to put skills, which fields are supported, etc. I'd love to be able to tell Codex what sort of sandboxing model I want and have it automatically configure that without needing to have it fetch the repo and look at the source.

- Make

/reviewa regular skill rather than the odd sort of packaged command it is right now. I want the model to be able to invoke it dynamically. - Nit: change the title of my terminal tab to something related to the task when executing. I frequently lose track of dozens of

codextitle tabs. - Have some sort of training specific to PR descriptions and commit descriptions. I generally like Codex's terse personality, but these could be expanded.

- Support

context: forkin skill definitions. - If a link overflows the line in the pane, it should still be clickable.

- Show my current worktree/PR/branch name at the bottom of the status bar.

Where this all goes

A few weeks ago, a friend sent me the post on Gas Town by Steve Yegge. It's still one of the wildest things I've read.

If you haven't seen it, Steve basically makes the case that you should just always be maxing out tokens. You should have a pool of workers, who are hungry to accept more work, and they should be going 24/7. You should make lots of plans. You should expect to throw them away.

For all your take on whether the abstractions are correct or not, directionally, I think Steve is absolutely correct.

The dream is to have your laptop (or cloud sandbox or whatever) constantly churning on ideas in the background, and have you be able to nudge it in directions, go off and do research, review its output and come back. Working with coding agents has made me feel much more like an engineering manager again when it comes to coordination, but without worrying about motivating the agents or the personalities involved.

Today it feels like we're quite a bit closer to that future. This is over-hyped on Twitter, but I do really try and kick off 3-4 tasks in Codex before going to bed, so they'll be ready for review in the morning. But I'm still not at the point where I feel like I can have agents running 24/7.

I think there are two barriers to more progress here...

- Context window size/coordination (see above). Agents can't endlessly compact/recycle in the same context window. We need either smarter harnesses or something which provides more delegation.

- Resistance to prompt injection. Sometimes the agents will only run for a few minutes before asking for an escalated approval. If I'm going to let them run overnight, I don't really trust them to run in

--yolomode, but there's a subset of sane permissions/domains I'd allow.

On the first point, Cursor has been pushing the bounds of what swarms of agents can do across many context windows. I still haven't seen great answers to the second, and it's an active area of research. Running in a sandbox seems like the best workaround for the moment, but this is still more painful to configure than it should be, and if there's privileged data that your agent has access to with open internet access, it's vulnerable to the Lethal Trifecta.

As a solo engineer working on projects, I'm already finding that I am the bottleneck when it comes to the right ideas. More and more, ideas, architecture, and project sequencing are going to become the limiting factors for building great products.